Archives

now browsing by author

CBC Outfront short “A Forgotten Master”

Ron Graner narrates the story of David Nowakowsky and the recovery of his lost musical manuscripts.

Near Loss and Heroic Rescue of Nowakowsky’s music

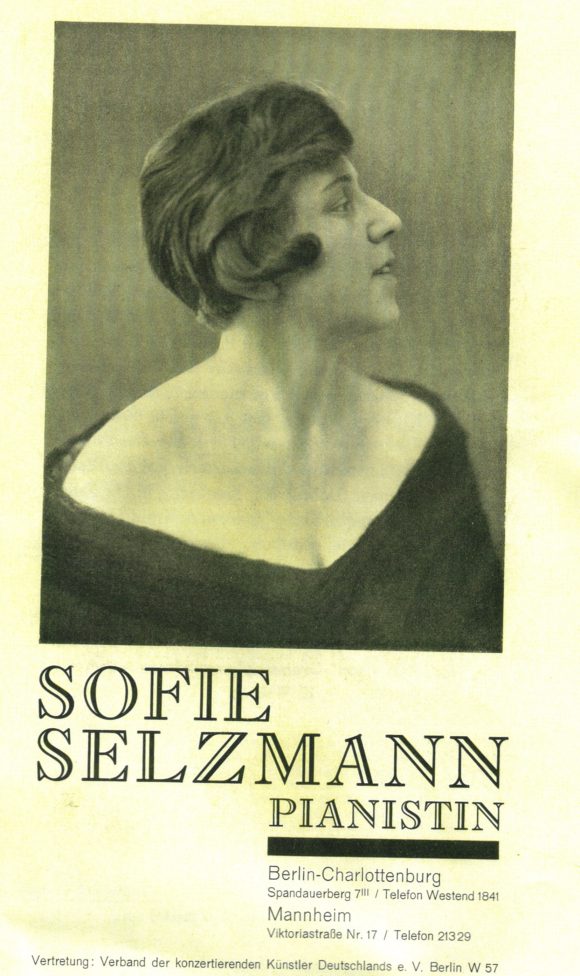

The pogroms of the earlier years would prove minor in comparison to what was to follow under the Bolsheviks. By 1924, with the city in a state of chaos, his daughter Rosa (Rachel) smuggled his works to her daughter, Sophia, (Sofie) who was then living in Berlin. Meanwhile the Brody Synagogue was closed, and converted into the town’s archives.

Later, both David Nowakowsky, and Sofie Seltzmann were included in the Nazi publication “Lexicon of Jews in Musik”.

Later, both David Nowakowsky, and Sofie Seltzmann were included in the Nazi publication “Lexicon of Jews in Musik”.

In 1937 granddaughter Sophia (Sofie) and her family became stateless refugees fleeing the Nazis without passports, moving from country to country using temporary travel visas called “laiser Passee”. While they were on the run, Nowakowsky’s unpublished manuscripts were stored in a warehouse in Strassbourg France. In 1939 Sophia’s husband, Boris, was able to obtain Romanian passports for the family, and they moved to the French village of Collonges-sous-Salève on the Swiss border just outside of Geneva. Now safely in so-called “Free France”. They retrieved the Nowakowsky manuscripts from the warehouse in Strassbourg and brought them to Collonges s/s.

One by one, the Zeltzmanns entered Switzerland. First to go was Sofie. In 1941 she was invited to give a concert on Swiss radio. Once there, her Romanian passport expired, and she could not return to France. Her husband Boris who had been working as an oil-company executive in Trieste, lost his job. He returned to Collonges-sous-Saleve and began a new career, selling bouillion cubes, so he could take care of his son, Alexandre. 7-year-old Alexandre could only meet occasionally with his mother at the barbed-wire fence separating France and Switzerland.

One day Sofie asked the French border-guard if she could take Alexandre to the cafe on the Swiss side of the border and treat him to a hot chocolate. The border-guard said “OK, but bring him back in 20 minutes.” The ruse worked! Sofie and Alexandre spent an anxious first night in Geneva, before reporting to the Swiss Guard the next morning. (Swiss police.) The Swiss policeman began filling out a long questionnaire. Halfway through he shrugged his shoulders, said: “It’s just a kid”, tore up the form and stamped Alexandre’s passport. He could stay with his mother!

Boris was not so lucky. In 1943 the Nazis entered Southern France to defend it from the Allies who had defeated General Rommel in Africa. Boris gave the precious manuscripts to the owner of the Chosal farm manor estate in nearby Archamps for safe keeping. Chosal, at first, hid them on the estate under some trash, but when the Nazis began to search local farms, looking for fugitives, and food supplies, he removed the incriminating crates of Jewish music from his estate, storing them out in the fields, half concealed by shrubbery. ” When my father returned to France after the war he asked the farmer, where are those crates of music that I gave you. [the farmer replied] It was too dangerous keeping them here… so I took them out to the fields. When my father saw them they were under a tree, next to a hedge, under (sic) the rain. Kids had found the crates, the lids pried open; papers scattered about. They [the kids] had tried to set them afire, but they were wet and wouldn’t burn. -and that’s what happened to the Nowakowsky manuscripts.” -Alexandre Zeltzman

Having disposed of the music, Boris then attempted an illegal entry into Switzerland. He was caught by the Swiss Guard, and interned in an old hotel that served as a jail for educated foreign detainees, who had university degrees. (lesser qualified detainees were sent to work-camps created from abandoned unheated military barracks.)

The prisoners were treated to concerts, the hotel was heated (to prevent the pipes from freezing), but food rations were meager and Boris when finally released, albeit under curfew, was much thinner than when he had gone in. During his incarceration, the prisoners organised classes among themselves. A professor of mathematics taught math and physics, Boris who had been a music student before studying business, served on the disciplinary tribunal, that regulated prisoner conduct. There were lessons in history, geology and literature etc. During this period Alexandre lived with his mother in a damp basement apartment and only saw his father infrequently as the hotel detention center was a distant and expensive journey from where they lived. Sofie suffered from bouts of pneumonia due to malnutrition, stress, and the unhealthy living environment. Boris petitioned for his release to take care of her and his son. Towards the end of the war he was indeed released, but was subject to a curfew that made it difficult for him to leave home or go to an evening concert. Neither Boris nor Sofie were allowed to work and subsisted on charity, from the Joint, (a Jewish relief organization), the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers), and an organization that provided help for “intellectuals” scientists and artists. (probably “The Germany Emergency Committee” founded by American journalist: Varian Frye. Unfortunately because of the secrecy in which the Germany Emergency Committee was forced to operate, there are no records confirming that the Seltzmanns (Zeltzman’s ) were clients of the organization.)

Without any healthy outlets for his boundless energy Boris’ personality changed from being a kind and even-tempered man to being angry, frustrated and hypercritical. After the war, Boris returned to his work at the oil company, (Aquila??) but at a lower executive level. Both Sofie and Boris died in the mid ’50’s. At the present time I do not know if Sofie was able to resume her concert career, or to what diseases ended their lives.

During my 1995 interview with Alexandre, with the exception of this brief comment on the change in his father’s personality, Alexandre made no mention of his parent’s personalities, politics or beliefs. His only said: “They were intellectuals.” As a consequence of this lack of any personal descriptions I had to portray them in my play: Musical Pawns, as purely fictional characters. Were they loving, distant, stern or supportive parents? I do not know. To my mind they were heroes, possessed with the wisdom to see into the political future and find ways to both save themselves and the precious manuscripts.

I was able to learn that Boris, when he worked in Trieste, provided the French military with intelligence on Fascist army deployments, reporting to an intelligence officer in Strassbourg during his frequent trips home. I also surmise that Boris chose to become a travelling salesman, selling bullion cubes to stores in the border areas, so he could continue his intelligence-gathering activities, by virtue of possessing a travel document, that allowed him to travel within occupied France. In effect he was “hiding in plain sight” as Jews were not allowed, under the notorious Nazi May laws, to possess bullion cubes. While in France he also cultivated good relations to the customs officials and the mayor of Collonges-sous-Saleve, many of whom were secretly active members of the Dutch-Paris Underground. His brother, living in Strassbourg joined the Maquis and was awarded a medal by the French government for his resistance activities. Boris also was quickly able to obtain French citizenship because of his service to France.

The music collection was brought to New York in 1953 when Alexandre attended Columbia University. The music was given to Hebrew Union College School of Sacred Music in New York in 1955. It’s composer-in-residence, Dr. Max Helfman was able to edit only six or seven works, before several influential members of the music committee died or retired and the project to publish the music died on the vine. Helfman died suddenly in 1963 of a heart attack in California. The last piece he wrote: “Songs for a Mourner’s Service” was published posthumously. It contains a setting of Chaim Bialik’s poem “When I am dead -Thus shall you mourn me. There is a man, and see he is no more …yet one more song he had within him.” Poet Bialik was Nowakowsky’s best friend, and wrote the epitaph on Nowakowsky’s tomb-stone. “There are many stars in the heavens, but none shone so brightly.” Thus the song contains both the words of Nowakowsky’s best friend and the music of his first post-war editor.

Hebrew Union College loses the manuscripts.

At first the collection was placed in the library for students to study, but when several works were not returned to the shelves, the Dean of the college ordered them stored in a basement room, housing the out-of-print music collection. These were all original manuscripts. There were no copies.

The boxes were wrapped in heavy black plastic, concealing their labels, and placed on a lintel over one of the doorways of the storage room.

Later when the Nowakowsky family asked for the music’s return the college couldn’t locate their location. The music remained missing for 13 years! The family was in the process of suing the college for the manuscripts return in 1979, when a cigarette butt was thrown into a waste-paper basket in the store-room, starting a small fire that set off the sprinklers. The insurance company inventory located the manuscripts. The black plastic wrappings which had at first, obscured the labels, were now responsible for protecting the priceless music from smoke and water damage. This was the 5th time the music had escaped being destroyed. Once by the Russians, then by the Nazis, then by French vandals and inclement weather, by theft from careless college students and now by smoke and water damage.

I was a student at the college at the time. My summer job was to try to salvage useable compositions from piles of wet, mouldy and disintegrating music stacked on the shelves and on the floors of the out-of-print music-storage room. The Nowakowsky collection was pointed out to me and I was told not to throw any of it away. Not even to look at them! Of course I looked at them as soon as the door closed. Then packed them up, labelled them, and sent them off to be stored in a secure facility -and promptly forgot about them.

I have often been accused of “discovering” the music. Nothing could be further from the truth. Previously as a chorister at Adath Israel Synagogue, I had sung one published composition by Nowakowsky, a short version of Psalm 115 which it seems was the only work of Nowakowsky’s that was used in the Synagogue service during one of the three annual festivals. None of the cantors or music directors I spoke to knew of any other Nowakowsky work. It was sung only at one or two of these 3 festivals each year, -if at all. -And only by synagogues that had good quality choirs.

The real champions of Nowakowsky’s music, besides his family, were 2 individuals.

In 1923 (?) Nowakowsky’s assistant organist: Israel Geller, walked out of Russia with a small collection of music that happened to be in the organ bench, when the Bolsheviks seized the Synagogue. He came to New York, where he became the organist at Park Avenue Synagogue and used some of that music in the service. Geller died in 1956 bequeathing his library to his colleague Cantor Cantor Robert Segal. When Segal retired in 1978 he bequeathed the library back to Park Avenue Synagogue.

The new cantor at park Avenue, was David Lefkowitz, a brilliant singer and musicologist. He recognized the exceptional quality of the music, and spent the summer editing the music to be performed at a special Friday night service with an augmented choir and organ. Faculty at HUC attended this service and informed Cantor Lefkowitz of the larger collection, (3,500 pages) that I had labelled and sent into storage, awaiting the completion of a new building to house the college. They asked David Lefkowitz if he would be interested in taking on the task of editing the music. I was home in Toronto at the time and knew nothing of the concert.

First the music had to be returned to the family. The David Nowakowsky Foundation was formed and David Lefkowitz became its Vice-President. It took Cantor Lefkowitz 10 years to edit the music. It’s first performance was in 1989 at Royce Hall, California, with the Roger Wagner Chorale and Orchestra. The Novack family had raised enough money to hire the orchestra and the soloists, but it would have cost another $100,000 to make a legal recording, so only archival tapes were made, so this wonderful concert could not be broadcast or the tapes sold.

In 1990 Cantor Lefkowitz addressed a Cantorial convention at Grossinger’s hotel on the concert and on Nowakowsky’s music. I was there but didn’t attend the lecture. I went swimming instead.

The next day, needing a ride back to New York, David offered me a lift. It was there in his car, that I first heard Nowakowsky’s symphonic, chamber and large choral works. I was hooked!

By this time I had been a full-time cantor for almost ten years. I had produced an ecumenical concert of Jewish Interest with the Edmonton Symphony Orchestra in 1985, that sold out and made my synagogue a substantial profit. What was missing from that concert was Jewish-themed orchestral music from the 19th century Romantic period. Nowakowsky’s music would have filled that void, had it been available. By 1990 it was available. David asked me if I could help the David Nowakowsky Foundation by publicizing the music. Like an idiot, I said “Yes”.

I soon learned that no newspapers, radio or TV stations were interested, unless there was an actual event that they could write or talk about. To get any notice, I had to give a talk or produce a concert.

Except from what I learned from David’s program notes, there was almost no information in any publications. A few short sentences in Jewish encyclopedias, each with different dates of his birth. One said he was born in 1847, another in 1848 and a third in 1849. One said he ran away from home on account of his step-mother, another that he was an orphan at age 12. Nothing was found in any standard musical text. Information provided by the Novack family was also just as confusing, as few in the family had kept track of their family histories. (It’s the same in my family.)

Norreen Green, a conducting student working on her doctorate in California, quoted David Lefkowitz’ research in her thesis. I was also in touch with David Novack, a film-maker in New York, descended from Nowakowsky’s half-brother. He and Norreen travelled to Odessa to attend a Ukrainian music seminar, and to film the Brody Synagogue and Nowakowsky’s final resting place. Norreen’s doctorate was in conducting, not in musicology. She was afraid to present in front of trained musicologists, but her talk on Nowakowsky became the hit of the conference. The Ukrainian Minister of Culture offered the famed Odessa Opera House as a venue for a dedicated concert of Nowakowsky’s music. I obtained one of six published copies of her thesis for my library, and the typwritten short reports Norreen and David submitted to the Foundation on their trip to Odessa were also provided to me.

The biggest breakthrough came when I contacted Alexandre Zeltzman in Paris in 1995 and spent 3 days recording the story of how his parents had saved themselves and the Nowakowsky manuscripts from destruction. Alexandre had kept meticulous notes organized in chronological order. Actor Vanessa Redgrave had provided me the means to travel to Paris, by inviting me to perform in London’s Hammersmith Auditorium at a festival she organized to celebrate the 50th anniversary of V.E. Day. (Victory in Europe.) My illustrated concert was called: From Genesis to Gershwin -a Musical History Tour. My small 75 seat venue quickly sold out, and I was moved to a larger hall seating 350 to accommodate the small overflow.

In 2006 Bravo Television’s BravoFact Foundation awarded me a grant of $20,000 to make a 5-minute short film and CBC Radio asked me to do a 13-minute documentary on the making of the film. My production partners were director: Jason Bourque and film producer: Ken Frith based in Vancouver. Concert-Master of the Toronto Symphony Mark Skazinetsky, cellist David Hetherington and organist/pianist Patricia Krueger provided the musical accompaniament . The short film won the Audience Appreciation Prize at the Chicago International REEL Short Film Festival in 2006.

A 2nd CBC radio documentary on Cantor Louis Danto was commissioned. Louis was championing the composers who had followed Nowakowsky. They were students at the St. Petersberg Conservatory who formed a Jewish music society in 1908 to compose new works. His beautiful singing brought accolades from around the world.

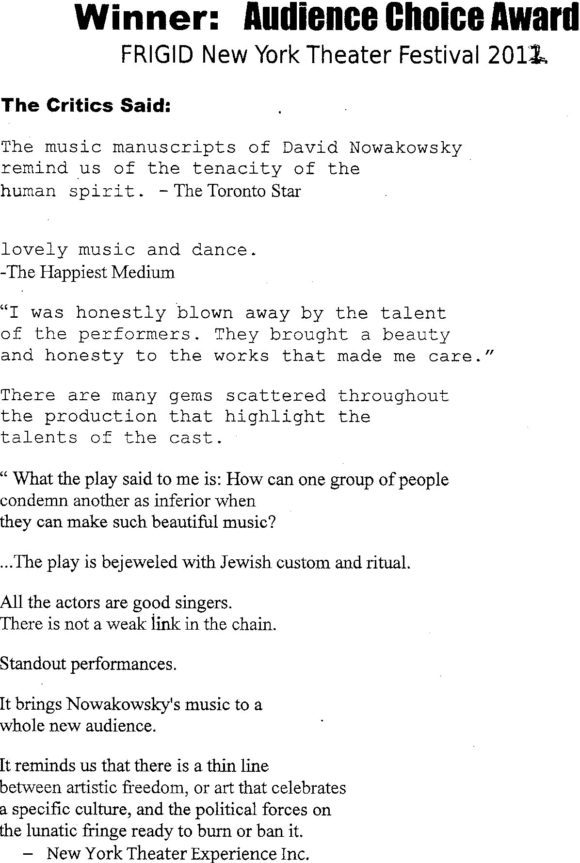

In 2012 I wrote and produced a musical play derived from the Nowakowsky story. The hard work and dedication of the singing actors and dancers was a key to it’s success. MUSICAL PAWNS won the Audience Enjoyment Award at the FRIGID New York Theatre Festival.

In 2012 I wrote and produced a musical play derived from the Nowakowsky story. The hard work and dedication of the singing actors and dancers was a key to it’s success. MUSICAL PAWNS won the Audience Enjoyment Award at the FRIGID New York Theatre Festival.

Shchedryk (2015) a short film on the assassination of composer: Mykola Leontovych, famous for Carol of the Bells, is currently touring the international festival circuit. Jazz pianist: Paul Hoffert improvised a version of Carol of the Bells. Editor Peter Gugeler managed the visual effects, and co-producer Kalli Paakspuu was the driving force, entering the short film in festivals around the world.

Musical Career

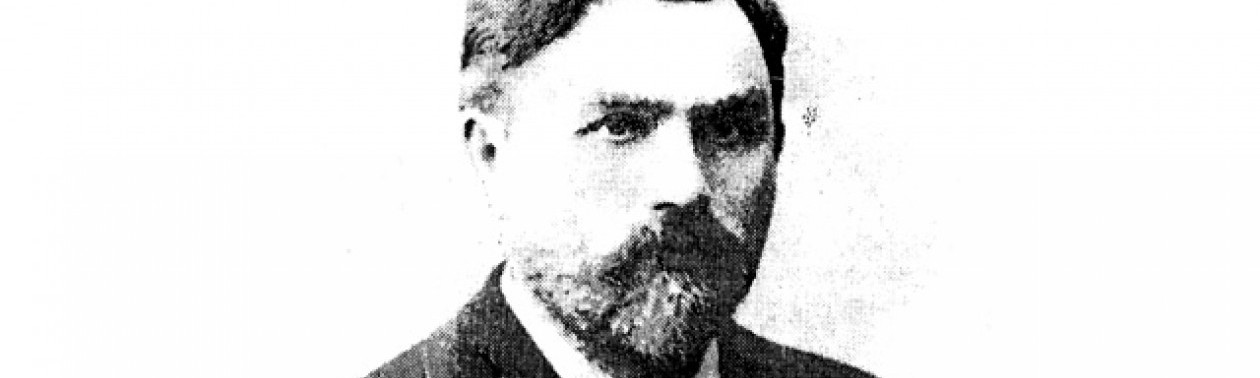

In 1869 Nowakowsky was offered the post of assistant conductor to Nissim Blumenthal at the newly built Brody Synagogue in Odessa, and to instruct in the choir school that Blumenthal had established.

Blumenthal had experimented with the use of western songs and the German language with traditional Jewish choruses. For instance, he used Handel’s “Hallelujah” chorus fromThe Messiah sung to the words of Psalm 113: “”Halleluhu: hallelu avdei adonai” (“Praise the Lord, O servants of the Lord”).

Nowakowsky followed this concept but used Hebrew instead, adapting Felix Mendelssohn’s Opus 91 setting of Psalm 98 for his chorus. This led to some fame for the synagogue, which was often visited by the nobility and the military elite simply to listen to the music. Their use of organ during services was soon picked up by larger synagogues, who’s members were visiting Brody.

The congregation expected to hear a new piece almost every week. Nowakowsky obliged and did so for 53 years. We can describe his output as follows: The bulk of his music is for the synagogue service, with members of the choir accompanying the Cantor who sang the solos. The choral works range from simple four-part harmony to up to 16 separate parts with organ and contrasting rhythms for the cantor’s solo voice. There were also instrumental works that were presented at concert halls, over 100 organ preludes, folk-song arrangements and German and Russian Lied.

Besides his work leading the choir, Nowakowsky also taught other cantors how to compose music. To do so he hand-wrote textbooks on harmony and counterpoint. Three of these instruction manuals are part of the archives now stored at the YIVO institute in New York. One is in German, another in Hebrew, and a third in the Russian language. Many of the students in his choir later became cantors themselves.

Although the David Nowakowsky Foundation thought we had all of Nowakowsky’s music, a researcher at Leeds University, discovered a previousluy unknown work in Johannesburg South Africa, taken there by one of Nowakowsky’s pupils.

Birth

Nowakowsky was born in Malyn in Ukraine in 1848, part of the Machnovska administrative area. Little of his early life is known, although there are several stories that survive. At 8 he left home, apparently due to the hounding of his stepmother, to sing in a trio with a cantor in the nearby town of Smelnik (Chmelnic? {Smelnik is apparently Ukrainian for “Drunkard”}). He was later orphaned and joined the choir of cantor Spitzberg (Spizbergen?) in Berditchev. The Berdichev choral synagogue was part of the enlightenment movement expounded by Rabbi Moses Mendelsohn in 1800. Mendelsohn thought that if Jews abandoned orthodox clothing, learned to speak proper German, rather than Yiddish, and modeled their services after Christian modes of worship, Jews would no longer be persecuted. Conservatory-educated Jewish composers, like Salomon Seltzer, and Louis Lewandowsky, wrote choral versions of Jewish prayers and anthems using western harmonies. They also simplified cantorial recitative and provided organ accompaniament, whereas traditional synagogues do not allow musical instruments to be played on the sabbath, in mourning for the loss of the Temple in Jerusalem, which did employ musical instruments.

The young Nowakowsky was exposed to this reform in Jewish music, but he also studied traditional Jewish liturgical modes with cantor Yerucham (HaKaton) Blindman, and organ, theory and counterpoint at the Conservatory in Berdichev. Years later, after Nowakowsky was recognized as a master composer, the roles were reversed. Blindman became Nowakowsky’s student of harmony and counterpoint. As his name suggests Yerucham (Jeremiah) Ha Katon (The little one) Blindman (Blind man). was a blind person of extremely short stature. He had an amazing voice, and performed with great musicality.

Thus Nowakowsky bridges two worlds. The world of traditional tunes sung to Jewish modes and the world of western classical music, and somehow manages to combine them both seamlessly.

D5 Creation

D5 Creation